WMF Martins Fontes Publisher

Jane Jacobs was a Canadian writer and activist born in the United States in 1916. She is best known for her book The Death and Life of Great American Cities, published in 1961, where she criticized urban renewal practices. She was an important figure in the emergence of the urbanism movement, which seeks to humanize cities and promote pedestrian-friendly streets.

Jacobs was critical of the "rationalist" planners of the 1950s and 1960s, especially Robert Moses, and of Le Corbusier's earlier work. She argued that modernist urban planning ignored and oversimplified the complexity of human lives in diverse communities. He was also opposed to large-scale urban renewal programs that affected entire neighborhoods and built highways in cities. She advocated mixed, dense development and walkable streets, with passers-by's "eyes on the street" helping to maintain public order.

Your ideas about urban planning and architecture, such as mixed-use development and the importance of public street life, have had a significant impact on urban planning and design.

Jane Jacobs passed away in 2006 in Toronto.

I. Orthodox Urbanism

II Howard's Garden City

In summarizing the development of contemporary urban planning theory, the author begins with Ebenezer Howard's Garden City. The Garden City was conceived as a new form of master planning, a self-sufficient city removed from the noise and grime of late 19th century London, surrounded by green belts of agriculture, with schools and housing surrounding a shopping centre, all designed in detail. and predetermined.

The Garden City would allow a maximum of 30,000 inhabitants in each city and required a permanent public authority to carefully regulate land use and ward off the temptation to increase commercial activity or population density. Industrial factories were allowed on the periphery, as long as they were disguised by green areas. The Garden City concept was first incorporated in the UK by the development of Letchworth and Welwyn Garden City and, in the US, by the suburb of Radburn, NJ.

Jane Jacobs traces Howard's influence through well-known American figures such as Lewis Mumford, Clarence Stein, Henry Wright, and Catherine Bauer, a set of thinkers Bauer referred to as "Descentrists." Decentrists proposed using regional planning as a means of alleviating the ills of congested cities, luring residents into a new life in low-density areas and suburbs, away from the crowded urban core.

Jacobs highlights the anti-urban biases of Garden City advocates and Decentrists, especially their shared intuitions that:

- communities should be self-contained units;

- mixed land use created a chaotic, unpredictable and negative environment; that the street was a bad place for human interactions;

- houses should face away from the street towards sheltered green spaces;

- superblocks fed by arterial roads were superior to small blocks with overlapping crossings;

- any significant detail should be dictated by an ongoing plan rather than shaped by organic dynamics;

- population density should be discouraged or at least disguised to create a sense of isolation.

I.II. The Radiant City by Le Corbusier

Jane Jacobs continues her analysis of orthodox urbanism with Le Corbusier, whose Radiant City concept envisaged twenty-four skyscrapers within a Grand Park. In only superficial disagreement with the low-density, low-height ideals of the Descentrists, Le Corbusier presented his vertical city, with 1,200 inhabitants per acre. His concepts, however, demonstrate that his ideas were an extension of the Garden City. They are:

- the superblock;

- regimented neighborhood planning;

- easy access by car;

- the insertion of large grassy spaces to keep pedestrians off the streets into the city itself, with the explicit aim of reinventing the stagnant urban center.

Jacobs concludes his introduction with a reference to the City Beautiful movement, which peppered downtown areas with civic centers, baroque avenues and monumental new parks. These efforts were inherited from other contexts, such as the unique use of public space disconnected from natural walking routes and the imitation of the Chicago World's Fair exhibition grounds.

II. The importance of the sidewalk

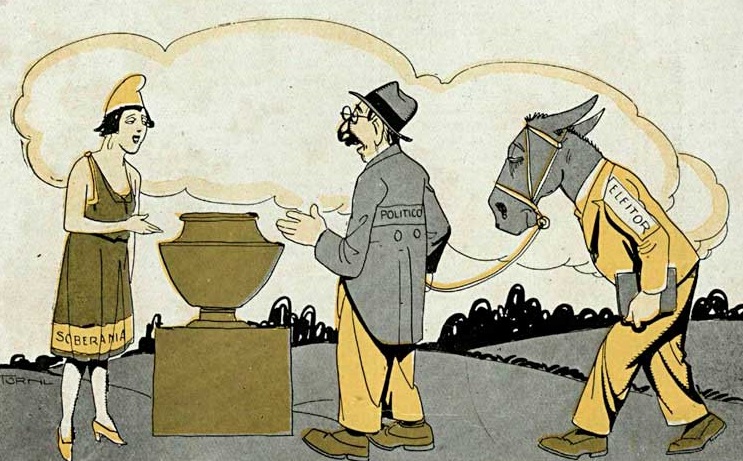

Jane Jacobs presents the sidewalk as a central mechanism in maintaining order in the city. “This order is all movement and change, and although it is life, not art, we can easily call it a kind of city art and compare it to dance.” For the author, the sidewalk is the everyday stage for an “intricate ballet in which individual and ensemble dancers have distinct parts that miraculously reinforce each other and make up an ordered whole”.

Jacobs places cities as fundamentally different from villages (or, in Brazil, districts) and suburbs, mainly because they are full of strangers. More precisely, the ratio of strangers to acquaintances is necessarily unbalanced wherever you go in the city, even outside your door, “because of the large number of people in a small geographic space”. A central challenge of the city, therefore, is to make its inhabitants feel safe, protected and socially integrated in the midst of a large volume of strangers in rotation. A healthy sidewalk is a critical mechanism for achieving these goals, given its role in preventing crime and facilitating contact with others.

Jacobs emphasizes that city sidewalks must be considered in conjunction with the physical environment that surrounds them. As she put it, “A city sidewalk by itself is nothing. It's an abstraction. It means something only in conjunction with the buildings and other uses that surround it, or that surround other sidewalks very close by”.

II.I. Security

Jane Jacobs argues that city sidewalks and the people who use them are active participants in fighting clutter and preserving civilization. They are not just “passive beneficiaries of security or helpless victims of danger”. A healthy sidewalk does not depend on constant police surveillance to keep it safe, but on an "intricate, almost unconscious web of voluntary controls and standards among people, and applied by people themselves." Jacobs suggests that a high volume of human users on the street deters most violent crimes, or at least ensures a critical mass of first responders to mitigate disorderly incidents. In other words, healthy sidewalks turn the city's high volume of strangers from a problem to a resource.

The self-enforcement mechanism is especially strong when streets are overseen by their “natural owners”, individuals who like to observe street activity, feel naturally invested in the unspoken codes of conduct, and are confident that others will support their actions, if necessary. They form the first line of defense for managing order on the sidewalk, supplemented by police authority when the situation calls for it. She concludes that three qualities are necessary for a city street to remain safe:

- a clear demarcation between public and private space;

- eyes on the street and buildings facing the streets;

- continuous eyes on the street to ensure effective surveillance.

Jane Jacobs compares natural homeowners to "passing birds," which is how she calls transient, disinterested residents who "don't have the slightest idea who takes care of their street, or how." Jacobs warns that while neighborhoods can absorb large numbers of these disinterested individuals, "if and when the neighborhood finally becomes theirs, they will gradually find the streets less safe, become vaguely baffled by it, and... leave."

Jacobs makes a comparison between empty streets and corridors, elevators and deserted staircases in public buildings with vertical housing. These “blind” spaces, modeled after upper-class living standards but lacking access control facilities, doormen, elevator operators, building management or related supervisory functions, are inadequate for dealing with outsiders and therefore the presence of strangers becomes “an automatic threat”. They are open to the public but shielded from public view and therefore “lack the controls and inhibitions exerted by the eye-guarded streets”, becoming springboards for destructive and malicious behavior. As residents feel increasingly insecure outside their apartments, they progressively withdraw from building life and exhibit “birds of passage” tendencies. These problems are not irreversible. Jane Jacobs claims that a project in Brooklyn successfully reduced vandalism and theft by opening hallways to public view, equipping them with play spaces and narrow porches, and even allowing tenants to use them as picnic areas.

Building on the idea that a pedestrian-friendly environment is a prerequisite for city safety in the absence of a vigilante contracted force, Jacobs recommends a substantial amount of shops, bars, restaurants and other public places “spread along the sidewalks” as a means to achieve that goal. She argues that if city planners continue to ignore sidewalk life, residents will resort to three coping mechanisms as streets become deserted and unsafe:

- leave the neighborhood, allowing danger to persist for those too poor to move elsewhere;

- retreat to the automobile, interacting with the city only as a driver and never on foot;

- Cultivate a sense of “territory” in the neighborhood by isolating yourself in upscale and unsavory environments using fences and security professionals.

II.II. Contact

Life on the sidewalk allows for a range of casual public interactions, from asking the shopkeeper for directions and advice, to waving at passersby and admiring a new puppy. "Most of these interactions are apparently trivial, but the sum is not trivial." Sum is “a web of respect and public trust”, the essence of which is that it “does not imply private commitments” and protects precious privacy. In other words, city dwellers know they can participate in sidewalk life without fear of “complicated relationships” or revealing details of their personal lives.

Jacobs contrasts this with areas without sidewalk life, including low-density suburbs, where residents must expose a greater part of their private lives to a small number of intimate contacts or settle for no contact at all. To sustain the former, residents need to be extremely careful in choosing their neighbors and associations. Arrangements of this sort, Jacobs argues, may work well "for self-selected upper-middle-class people," but they don't work for anyone else.

Residents in dead-end sidewalk spaces are conditioned to avoid basic interactions with strangers, especially those of different income, race, or education levels, to the point where they cannot imagine having a deep personal relationship with people so different from themselves. This is an impossible choice on any busy sidewalk, where everyone is treated with equal dignity, priority and encouragement to interact without fear of compromising their privacy or creating new personal obligations. As such, suburbanites ironically tend to have less privacy in their social lives than their urban counterparts, as well as drastically reduced acquaintances.

II.III. assimilation of children

Sidewalks are great places for children to play under the general supervision of parents and other natural street owners. More importantly, the sidewalks are where children learn the “first fundamental of successful city life: People should have a minimum public responsibility to each other, even if they have no ties to each other”. In countless smaller interactions, children absorb the fact that the natural owners of sidewalks are invested in their safety and well-being, even without ties of kinship, close friendship, or formal responsibility. This lesson cannot be institutionalized or replicated by hired help, as it is essentially an organic and informal responsibility.

Jacobs claims that sidewalks that are thirty to thirty-five feet wide are ideal, able to meet any demand for general play, trees to shade activity, pedestrian movement, adult public life, and even loitering. However, she admits that such width is a luxury in the age of the automobile, and finds solace that twenty-foot walkways – precluding rope-skipping play but still capable of lively mixed use – can still be found. Even if it lacks adequate width, a sidewalk can be an engaging place for children to congregate and thrive if the location is convenient and the streets are interesting.

III. The role of parks

Orthodox urbanism defines parks as “benefits given to needy populations in cities”. Jane Jacobs challenges the reader to reverse this relationship and "regard urban parks as underserved places that need the benefit of life and the appreciation bestowed upon them." Parks become lively and successful for the same reason sidewalks do: “because of functional physical diversity between adjacent uses, and therefore diversity between users and their schedules.” Jacobs offers four principles of good park design

- complexity (encourage a variety of uses and repeat users);

- centering (a major crossover point, pause point, or climax);

- access to sunlight;

- enclosure (the presence of buildings and a diversity of environments).

The fundamental rule of the neighborhood sidewalk also applies to the neighborhood park: “animated and varied attract more animation; death and monotony repel life.” Jacobs admits that a well-designed park at the focal point of a lively neighborhood can be a huge boon. But with so many worthy urban investments going unfunded, Jacobs cautions against "wasting money on parks, playgrounds, and land-use projects that are large, frequent, perfunctory, poorly located, and therefore too tedious or inconvenient to use."

IV. the city's neighborhoods

Jane Jacobs criticizes orthodox urbanism for seeing the city's neighborhood as an isolated, modular group of about 7,000 inhabitants, the estimated number of people to populate an elementary school and utilize a neighborhood market and community center. Rather, Jacobs argues that a feature of a large city is mobility of residents and fluidity of use across diverse areas of varying size and character, not modular fragmentation. Jacobs' alternative is to define neighborhoods at three levels of geographic and political organization:

- city level

- district level

- street level.

New York City as a whole is itself a borough. The main local government institutions operate at the city level, as do many social and cultural institutions – from opera societies to public unions. At the opposite end of the scale, individual streets – such as Hudson Street in Greenwich Village – can also be characterized as neighborhoods. City street-level neighborhoods, as argued elsewhere in the book, must aspire to have a sufficient frequency of commerce, general vitality, use and interest to sustain public street life.

Finally, the Greenwich Village district is a neighborhood itself, with a shared functional identity and common fabric. The primary purpose of the district neighborhood is to mediate between the needs of street-level neighborhoods and the allocation of resources and policy decisions made at the city level. Jacobs estimates the maximum effective size of a city district at 200,000 people and 1.5 square miles, but he prefers a functional definition over a spatial definition: "big enough to face city hall but not so big that street neighborhoods are unable to draw the attention of the district”. District boundaries are fluid and overlapping, but are sometimes defined by physical obstructions such as major roads and landmarks.

Jane Jacobs defines neighborhood quality as a function of how well it can govern and protect itself over time, employing a combination of residential cooperation, political influence, and financial vitality. Jacobs recommends four pillars of effective city neighborhood planning:

- Foster lively and interesting streets

- Make the fabric of the streets a continuous network as much as possible

- Using parks, squares and public buildings as part of the fabric of the streets, intensifying the complexity and multiple uses of the fabric instead of segregating different uses

- Fostering a functional identity at the borough level Jacobs is particularly critical of urban renewal programs that have demolished entire neighborhoods, as is the case in San Francisco's Fillmore district, creating a diaspora of its displaced poor residents. She argues that these policies destroy communities and innovative economies, creating isolated and artificial urban spaces.

V. Alternative Proposals

In their place, Jane Jacobs described “four diversity generators” that “create effective economic wells of use”:

- Primary mixed use, activating the streets at different times of the day

- Short blocks, allowing high pedestrian permeability

- Buildings from different eras and states of conservation

- Density

Their aesthetic can be seen as the opposite of that of the modernists, championing redundancy and vitality against order and efficiency. She frequently cites New York City's Greenwich Village as an example of a vibrant urban community. The Village, like many similar communities, may have been preserved, at least in part, by its writing and activism.

SAW. FAQ (Frequently Asked Questions)

- What is “The Death and Life of Great American Cities”?

“The Death and Life of Great American Cities” is a book written by writer and activist Jane Jacobs in 1961. It is a critique of the urban planning policy of the 1950s, which she considered responsible for the decline of many neighborhoods in cities across the United States. - Who is Jane Jacobs?

Jane Jacobs was an American writer and activist who distinguished herself as a critic of urbanism and a civil rights activist. She was known for her criticism of the rationalist urbanists of the 1950s and 1960s, especially Robert Moses, and the earlier work of Le Corbusier. - What is Jacobs's central critique of modernist urban planning?

Jacobs argued that modernist urban planning ignored and oversimplified the complexity of human lives in diverse communities. She opposed large-scale urban renewal programs that affected entire neighborhoods and built highways in cities. Instead, she advocated dense mixed-use development and walkable streets, with the “eyes on the street” of passers-by helping to maintain public order. - Who were the orthodox urban planners criticized by Jacobs?

Jacobs was critical of the "rationalist" urban planners of the 1950s and 1960s, especially Robert Moses, as well as the earlier work of Le Corbusier. She described prevailing urban theory as an “elaborately learned superstition” that had now penetrated the thinking of urban planners, bureaucrats and bankers in equal measure. - How did Jacobs propose that cities be planned?

Jacobs proposed urban planning that valued local communities and was sensitive to the needs and preferences of residents. She emphasized the importance of mixed use and density, walkable streets, and the inclusion of green spaces. She also highlighted the importance of local details and organic evolution rather than relying on permanent blueprints imposed from above.

SAW. Bibliography

- The Death and Life of Great American Cities (Modern Library (hardcover) ed.). New York: Random House. February 1993 [1961]. ISBN 0-679-60047-7. This edition includes a new foreword written by the author.

- Insights and Reflections on Jane Jacobs' Legacy. Toward a Jacobsian theory of the city

- Robert Kanigel (2016). Eyes on the Street: The Life of Jane Jacobs. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 9780307961907.

This text is a translation made by arqBahia of the article The Death and Life of Great American Cities – Wikipedia.

1 thought on “resumo do dia: Morte e vida de grandes cidades de Jane Jacobs”